This blog post was authored by Britany Green, a student in Professor Eckelmann Berghel’s HIST 3475: Modern Civil Rights Struggle class that curated an exhibit on display in the George Connor Special Collections Reading Room, located in room 439 of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Library in Spring 2019.

Before researching the history of Black Power movement in Chattanooga, I knew very little about the topic as a whole. I educated myself on the aims of the national Black Power movement, then I turned to Special Collections at UTC to see how members of the local community responded to the idea. With limited sources, the task seemed daunting at first; however, the materials I analyzed in the archives contained great depth and a richness that conveyed exactly what the Black American community of Chattanooga wanted.

After my other group members researched separately, we came together to decide on the theme and structure of the exhibit. We all agreed on the fact that the Black Power movement in Chattanooga focused on certain, critical aspects that we must feature on the display panel such as local groups’ community survival programs. We decided to format our project based on a list of eight demands published in a 1970 edition of a local Chattanooga newspaper, the Black United Front. The eight points clearly defined what the Black community needed to do in order to combat the systemic racism they suffered from daily.

Popular conceptions often connect the Black Power movement with violent and negative images. However, the movement mainly focused on the advancement and equal opportunity for Black Americans. Black Power meant that Black people took matters into their own hands, and they demanded equal access to housing, jobs, and education. The pieces we chose to include in our exhibit reflected these exact principles. During my individual research, I encountered a multitude of pieces that embodied the spirit and goals of the movement. I developed two themes for the exhibit on the struggles for better education and political representation, but I encountered many other important sources that did not get incorporated into the final exhibit.

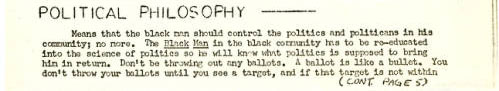

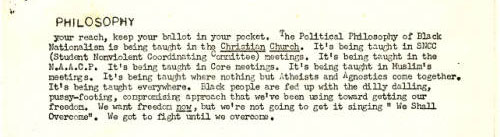

In an article titled “Political Philosophy” from a 1969 edition of local newspaper, the Black Fist, an anonymous author encouraged the readers to vote and make their voices heard. “A ballot is like a bullet,” claimed the author; he urged Black Americans to involve themselves in politics in order to make change. The author asserted that organizations like the NAACP and SNCC had been spreading Black Power ideology, and it meant that the Black community would no longer remain silent.

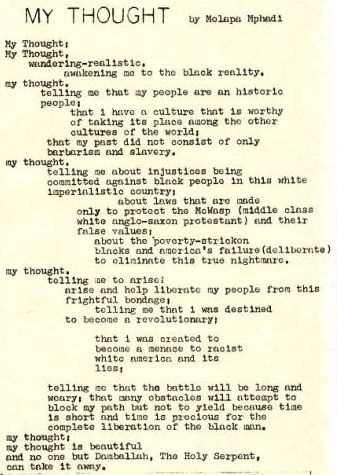

Other pieces in local Black Power newspapers featured more personal viewpoints on the movement. A Black United Front paper from 1970 contained a poem written by Molapa Mphadi titled “My Thought.” This poem discussed the oppression of Black Americans throughout history, but most importantly, it reclaimed of African American cultural roots. The Black Power movement stressed the idea of taking back one’s own culture and not allowing the past to define the Black American experience. Mphadi wanted readers to focus on celebrating one’s culture rather than allowing white America to silence this rich heritage, as Americans have done in the past. The author created this piece as a rallying cry for Black Americans, as she wanted them to know that their voices mattered in shaping the future of American society.

I chose to mention these two pieces here because they illustrate that the Black Power movement in Chattanooga spoke to a larger, national movement. The movement in Chattanooga not only wanted the Black community to feel unified on a local level, but also connect to national issues. It focused on racial pride in the Black identity and the importance of realizing that Black Americans experience the similar forms of oppression. Black Power meant that Black people recognized their own power to create change and demand that they be granted the equal rights that they had been denied for too long.