“It is no wonder Scotland is the birthplace of geology,” Dr. Mies said in class one afternoon. The lecture had ended, but many in the class always stayed after to discuss what Scotland would be like and to hear the stories of Dr. Mies’ prior travels. He showed us pictures of his past visits to Scotland and reveled in how each photo was received with awe by his students. When we finally visited Scotland, we found that the pictures that looked to be taken from a fantasy novel did no justice to the geologic scale of Scotland. Words cannot describe the beauty of Scotland, and apparently, neither can pictures. Dr. Mies’ statement months prior to our trip stuck with me throughout the whole of my experience abroad. It is no wonder Scotland is the birthplace of geology.

The Scottish Enlightenment brought on an age of understanding and innovation in the sciences. James Hutton, the father of geology, was one such contributor. After studying medicine, he headed out into the country to oversee his family farm where he noticed the cyclic cycle of the earth at play. Hutton saw that the rivers were carrying away his farmland and soil, but the common view of the time was Earth was not dynamic, so how is there still soil left? He started writing about these processes and concluded that the Earth must be older than the current belief of 6000 years. But how could he prove it?

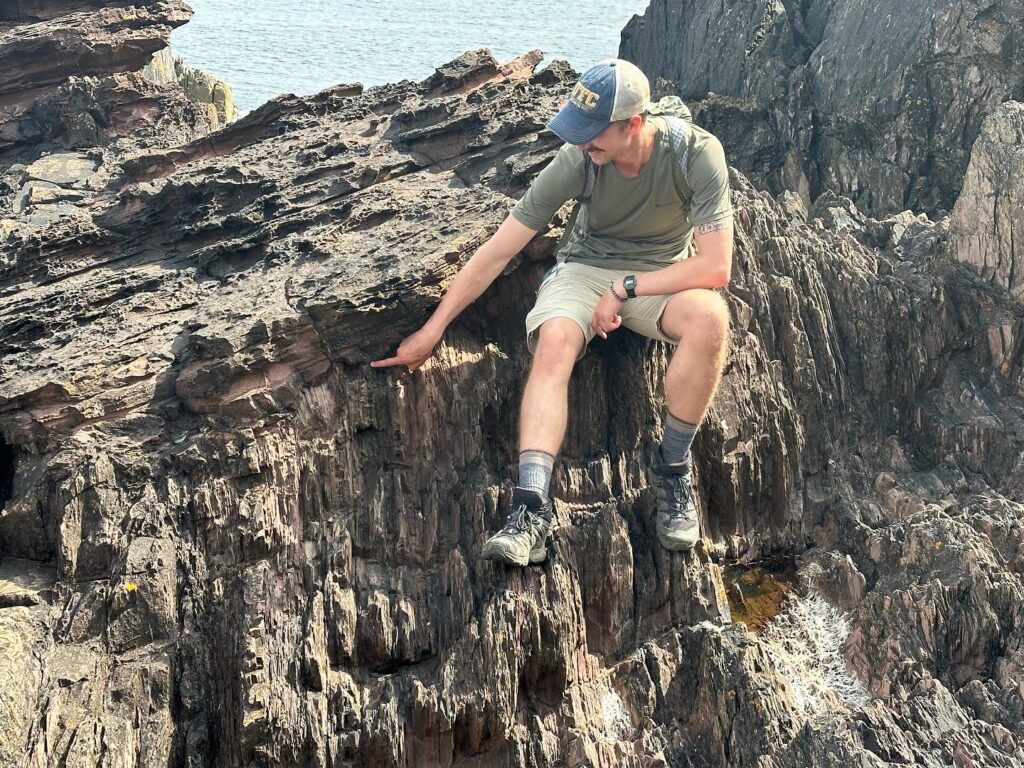

Seeing Siccar Point in person is something like a spiritual awakening as a geologist. This rock formation is the start of the study, the beginning of Geology as a science. It is how Hutton proved his “Theory of the Earth” and the golden poster boy of unconformities. Here, two very different rock units but up against each other, but in different orientations. The older rock lays vertical, T-boning the younger red sandstone which lays closer to parallel. Hutton wondered how this could have happened in a world that is only 6000 years old. The process of flipping a rock unit and depositing new rock on top must take ages or even eons. It was the evidence he needed for his research and the defining formation which helped cement his perspective within the Scottish Enlightenment. Here, at this most holy of locations for geologists, we unpacked lunch and broke bread around the start of our science.

As a geologist, it is easy for me to forget about the societal history of an area. I learn about the volcanisms, tectonic history, or oceanographic past of a city, and completely brush past the historic past of the people who call it home. However, my trip to Scotland opened my eyes to how the geology of an area changes how people live, how languages evolve, and how relationships between clans thrive or dissolve. Scotland’s natural beauty cannot be separated from the Highlander’s history. One such example is our visit to Stirling Castle. Stirling Castle sits atop an intrusive crag part of the Stirling Sill formation. In the geologic past, a great welt of lava had pushed through the surrounding rock deep underneath Scotland and cooled. The rock around this body of lava was subsequently eroded, leaving an enormous cliff erected above the fields of Scotland.

When a powerful clan family wants to build a castle, they look for certain landscapes. A castle must be defensible, but easy to get to and trade from. It must be set above the commoners so everyone in the land can be reminded of the family’s power, but not too far away for the family’s influence to be felt. Stirling Sill must have looked like a golden opportunity for the Stirling family to build their castle. It has a shallow slope which drops off on all sides by shear cliffs. It is defensible, easy to get to, and sits in the middle of a large meadow. This view of how geology forms human habits and cities is not something I thought about throughout my undergraduate career but was always on my mind in Scotland. Every city was set up according to what was permitted by the surrounding geology.

Scotland has a deep and rich history. It is an anthology of rock throughout Earth’s history and has housed a prominent culture for thousands of years. The importance to me of seeing Scotland in my last summer as a geology undergrad cannot be understated. As I move on to grad school, this trip will stay with me for the rest of my life and will remind me of where my science started, and where I might take it.

Evan Ritchey (BS Geology) spent part of July 2023 participating in a faculty-led trip to Scotland with the Geology department. Evan had the following to say about studying abroad, “Scotland is a record of eons. The landscape holds secrets of ancient continents and more recent cultures. I want to thank the Office of Study Abroad for supporting my travels and letting me discover Scotland in person.“

Share this post:

Leave a Reply